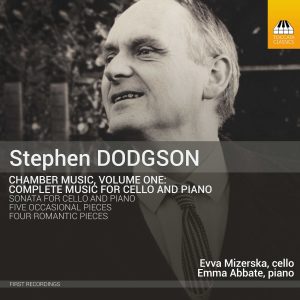

DODGSON 2 Romantic Pieces: Set A, Set B. Cello Sonata. 5 Occasional Pieces • Evva Mizerska (vc); Emma Abbate (pn) • TOCCATA 0353 (67:21)

As the English composer Stephen Dodgson (1924–2013) is hardly a well-known figure, Toccata Classics’ always informative liner notes are especially welcome, including the various appreciations of the music which followed his death at the age of 89. For the recorderist John Turner, for whom Dodgson wrote a fair number of pieces, “stylistically, his music is tonal, though often ambiguously so. Like that of Janáček, a composer he admired and whose compositional method of developing small cells finds its echo in his own works, the music rarely follows an obvious path. Performers find initially that the music is surprising and unexpected—puzzling even—and almost always very intricate….However, once the music reveals its secrets, it becomes intensely appealing. The influence of early music in his style manifests itself in numerous ways: not just in his choice of instrument, but also in his love of decoration and ornamentation, a fondness for virtuoso display, baroque-style figuration, a predilection for variation form (often on medieval or folk-tune themes)….” Perhaps more objectively, there was this from Guy Rickards in Gramophone: “His often angular melodies have a knack of registering in the memory and are beautifully laid out for the instruments. He had a romantic side, with lilting themes….His mature style was one of refinement, sitting somewhere between post-Romanticism and Neoclassicism but individual works often varied this blueprint, having quirky, even spectral sides to them.” All of the above is abundantly on display in this album of Dodgson’s complete music for cello and piano written between 1969 and 2008.

As the English composer Stephen Dodgson (1924–2013) is hardly a well-known figure, Toccata Classics’ always informative liner notes are especially welcome, including the various appreciations of the music which followed his death at the age of 89. For the recorderist John Turner, for whom Dodgson wrote a fair number of pieces, “stylistically, his music is tonal, though often ambiguously so. Like that of Janáček, a composer he admired and whose compositional method of developing small cells finds its echo in his own works, the music rarely follows an obvious path. Performers find initially that the music is surprising and unexpected—puzzling even—and almost always very intricate….However, once the music reveals its secrets, it becomes intensely appealing. The influence of early music in his style manifests itself in numerous ways: not just in his choice of instrument, but also in his love of decoration and ornamentation, a fondness for virtuoso display, baroque-style figuration, a predilection for variation form (often on medieval or folk-tune themes)….” Perhaps more objectively, there was this from Guy Rickards in Gramophone: “His often angular melodies have a knack of registering in the memory and are beautifully laid out for the instruments. He had a romantic side, with lilting themes….His mature style was one of refinement, sitting somewhere between post-Romanticism and Neoclassicism but individual works often varied this blueprint, having quirky, even spectral sides to them.” All of the above is abundantly on display in this album of Dodgson’s complete music for cello and piano written between 1969 and 2008.

Clearly, the most important work here is the Sonata for Cello and Piano from 1969, one of Dodgson’s rare forays into Classical form. (In his superb notes, John Warrick tells us: “With the striking exception of the seven piano sonatas, written at fairly regular intervals throughout his career between 1969 and 2003, Dodgson was generally drawn to pre-Classical forms and so tended to avoid the title ‘sonata’ and the use of Classical sonata form….”) Beginning with a dotted-note theme that bears a striking resemblance to Percy Grainger’s Country Gardens, the opening movement—marked Con anima—certainly does move very vigorously, with both instruments playfully competitive and often playing against type (witness the cello’s pizzicato chords that accompany the piano’s jaunty principal theme). The slow movement is a pensive nocturne in which the composer’s fondness for ambiguous tonality is evident throughout; the effect is vaguely unsettling—in a very positive sense—suggesting an admiration for the music of Béla Bartók as well. Unsettled rhythms also drive the finale, which begins as an intricate, tightly-woven partnership but ends with every man/woman for him/herself. While the obviously talented Evva Mizerska plays with skill and conviction, one wonders what it would sound like in the hands of seasoned players like Raphael Wallfisch or Paul Watkins, who should certainly be encouraged to include it in the next installment of his Chandos survey of British cello sonatas as it sounds, unmistakably, like a major work.

Dodgson’s fondness for Janáček is most apparent in the quirky “Capriccioso,” the first of the Two Romantic Pieces (Set A) from 1996. The capriciousness, here, comes in the form of rapidly shifting emotions, though it’s the singular, deeply-felt emotion conveyed in the second piece, Poco lento, that makes it even more memorable. In 2008, Dodgson added a second pair of Romantic Pieces: a fizzing scherzo and an elegantly decorated Moderato flessibile, in which the cello’s sinuously flexible singing lines are key.

If the title suggests something a bit more slight, then the Five Occasional Pieces from 1970 are anything but. The composer tells us: “Written while the composition of the Sonata was still a fresh experience, these are intended to be definitely cello pieces with piano, as opposed to the essentially duo style of the Sonata. This applies particularly to the last three movements, the Alla Polka making a light-hearted virtuoso conclusion. The deepest moment is perhaps the Dialogue, with nervous irregular rhythms, tender moments and sudden explosions. At the tenderest moment of all, the principal motif grew spontaneously so close to the important muted trumpet/cor anglais phrase [why do Englishmen always insist on calling the English horn that?] from the introduction to Debussy’s La Mer, that I allowed it to state its whole outline. The Aria is an attempt to write a long developing line with sustained accompaniment, a much more difficult type of movement to write in 1970, it seems to me, than the nervous Dialogue type, or the ironic Burlesca.”

If one might have wished for a bit more character—especially in terms of dynamic shading—here and elsewhere, then the performances are more than good enough to suggest that Five Occasional Pieces, like the other works on the album, are the products of an original, highly distinctive, consistently surprising voice, making what is now the only collection devoted entirely to Dodgson’s music long overdue.

Jim Svejda

This article originally appeared in Issue 40:4 (Mar/Apr 2017) of Fanfare Magazine.