Interview of Julian Perkins by Katherine Cooper, Presto Classical

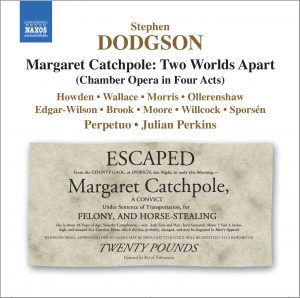

Composed in 1979, Stephen Dodgson’s four-act chamber-opera Margaret Catchpole tells the real-life story (with a dash of artistic license) of a Suffolk maidservant who was convicted for horse-stealing and deported to Australia at the end of the eighteenth century. The work received a handful of performances during the composer’s lifetime, but never achieved the recognition it deserves; on the day before his death in 2013, Dodgson observed to his wife Jane that ‘we must do something about Margaret Catchpole‘.

Eight years on, the opera received its world première recording under the direction of Julian Perkins at Snape Maltings, with the young Australian mezzo Kate Howden in the title-role. I spoke to Julian about his friendship with Dodgson and his widow, the imaginative depictions of contrasting characters and landscapes in the opera, the composers whose influences can be felt in the soundworld of Margaret Catchpole, and plans for more recordings of Dodgson’s music…

How did your relationship with the composer and his music begin?

Photo: Luke Koch de Gooreynd

In a roundabout way it was through the harpsichord, really, that I came to know Stephen. I initially got talking to his wife, the harpsichordist Jane Clark, during my student days, when I was giving a private house-concert on the harpsichord for a friend in Paddington, and shortly afterwards they came along to another recital I did at what’s now called the Handel & Hendrix House in Brook Street. I already knew of Jane from my undergraduate work because she’d written various articles about Domenico Scarlatti, so we got talking about that, and then I visited them at their lovely house in Barnes and enjoyed their excellent hospitality on numerous occasions! Then I recorded the two clavichord suites that Stephen had revised and performed a chamber piece he wrote for my baroque ensemble. It was through that relationship that Margaret Catchpole ultimately came about.

Do you have any theories as to why the opera lay in the shadows for so long?

Jane once told me that Stephen was (and I quote) ‘infuriatingly disinterested’ in what he’d written! I think it was a really a case of his eye always being on the next project, which is fairly typical of a lot of composers in that they tend to live for the next commission rather than being especially concerned with their legacy. I’ve thought for a while that there should really be a festival of second performances: all the focus has always been on the première of a work, which all too often ends up being the dernière as well!

Yes, I believe he was: he wrote lots of music for BBC drama productions, and there was a comic opera called Cadilly, which predates Margaret Catchpole, and was going to be performed at the Barnes Festival this year. The libretto is by the brother of Antony Hopkins (the composer and broadcaster, not the actor, that is!). It’s quite interesting scoring, for voices and winds; he also wrote a work for voice and horn trio, which to my knowledge is unique in the repertoire. And the sixteen roles in Margaret Catchpole are all very well-differentiated: there’s an enormous amount of variety in the vocal writing and characterisation, which is quite Britten-esque in places.

Britten was of course another composer who drew operatic inspiration from the Suffolk landscape and its people – did Stephen have any contact with him?

I think they certainly knew of one another – I know that Stephen went to a very early performance of Peter Grimes – but there was no direct contact. I never met Britten, of course, but I get the impression that he was quite a difficult man to get to know. But there were definitely influences at work: Stephen loved Billy Budd and The Turn of the Screw (not so much Death in Venice, apparently, because of its emotional content), and I think you can hear that in the scoring of Margaret Catchpole. Like The Turn of the Screw, it’s a chamber opera, and it inhabits a similar sound-world. In fact I think I heard somewhere that Britten read the story of Margaret Catchpole at one point, but didn’t get any further than that…

Britten aside, which other composers do you feel Stephen drew on in his operatic work?

I think Janáček was a big influence on him in terms of the way he treats text – and in terms of Margaret Catchpole specifically, the English folk-song tradition was very important as well; I feel that he was also inspired by the sensitivity to English word-setting that you find in Purcell, as indeed was Britten. In fact anyone who’s written an opera in English probably owes a debt to Purcell in that regard.

Australia is fairly unusual terrain for operatic composers: what were Stephen’s connections with the country, and how does he rise to the challenge of depicting its landscape?

Stephen was fascinated by the idea of Australia, even though he never actually went there – it’s rather like Shéhérazade, where Ravel depicts places he’d never visited. (Stephen set Australian poems in his Bush Ballads, a group of three song cycles which I believe has now been recorded.) I think he relished the opportunities to depict the two very different landscapes in Margaret Catchpole, and responds to the contrasts between light and darkness in a most imaginative way: the first three acts of the opera depict the moody marshes of Suffolk, while the fourth and final act is set in the open, sunlit landscapes of Australia. The tonality plays a key role in that, especially at the beginning of Act Four: it’s never in a clear key, but there’s a tendency towards bright, sharp tonalities. And there’s a certain rhapsodic quality to the music there, too – it’s almost like a waltz, even though it’s actually written in 4/4.

Can you pick out two or three more personal highlights from the score?

I think that one of the most interesting characters is Crusoe, who is a half-crazed fisherman/mystic in the Peter Grimes tradition, and his entrance to me is so effective because you have this rather eerie-sounding tenor voice singing lean lines which seem to arise from the misty marshes. I remember going on walks in Suffolk which really brought home to me how evocative Stephen’s writing is there: the contrast between the richness of the orchestration and the austerity of the vocal line is so striking. And then in terms of compositional variety I must mention the judge at the beginning of Act Three, where the vocal writing is very strident and driven, with a lot of rather pompous dotted rhythms – we were very lucky to have the wonderful Matthew Brook in the cast for this role, who was fantastically imperious!

I think that one of the most interesting characters is Crusoe, who is a half-crazed fisherman/mystic in the Peter Grimes tradition, and his entrance to me is so effective because you have this rather eerie-sounding tenor voice singing lean lines which seem to arise from the misty marshes. I remember going on walks in Suffolk which really brought home to me how evocative Stephen’s writing is there: the contrast between the richness of the orchestration and the austerity of the vocal line is so striking. And then in terms of compositional variety I must mention the judge at the beginning of Act Three, where the vocal writing is very strident and driven, with a lot of rather pompous dotted rhythms – we were very lucky to have the wonderful Matthew Brook in the cast for this role, who was fantastically imperious!

And we mustn’t forget Margaret herself, who has a wonderful aria with harp in Act Three when she’s reminiscing about her former lover – the direction in the score is that it should be sung ‘with rapt calmness’, and it really does capture the vulnerability of the character quite beautifully.

This recording was made from concert-performances: do you think that the piece has a future on stage?

I think it would be very interesting to stage, yes – it has a fairly large cast, but essentially it’s a chamber piece that could fit quite easily into a space like the Britten Studio at Snape Maltings, where we recorded. Staging the orchestral passages depicting Australia would be a challenge, but I’m sure a talented director would relish the opportunity. It’s also a very relatable story in many respects, and one which was fairly well known in Suffolk in particular: I’m not from the area myself, but I was speaking to a radio-producer in Suffolk about the recording just the other day and she gave me the impression that a lot of her listeners would know Margaret’s story already. There’s even a Margaret Catchpole pub in Ipswich!

Do you have plans to record more of Stephen’s music?

Yes, and there’s something already in the pipeline – last November I recorded some of Stephen’s piano duets with my wife Emma Abbate for BIS Records. There are two suites and a sonata for piano duet, and this will be their world première recording: it was produced in association with the Stephen Dodgson Charitable Trust and the Lennox Berkeley Society, and it’s been a great lockdown project. Hopefully it won’t be too long before we can perform these pieces in public again…

Julian Perkins was interviewed by Katherine Cooper for Presto Classical

![]()