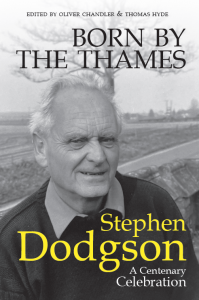

Born by the Thames

Stephen Dodgson: A Centenary Celebration

edited by Oliver Chandler and Thomas Hyde

Published 2024

Paperback, 297 pages

ISBN 987-1-8383269-1-3

de la Porte Publishing

In the autumn of 1969, like most of my friends, I was busy trying to organise what to do after ‘A’-levels. I was lucky because, for me, music was the only possible choice, and even more fortunate that my application to the Royal College of Music was successful. And so, when the train for London pulled out, I seemed to be taking my first steps towards a career as a professional composer. I had requested as my teacher someone whose music I had never heard, though I knew he had written a guitar concerto, and his vaguely American-sounding name was an added touch of glamour. My wish – which I put down to youthful arrogance – to take piano lessons from Lamar Crowson had been refused, and in spite of this I did not appreciate the extraordinary privilege of having Stephen Dodgson as my teacher. I studied with him for three years at the College and then, intermittently, for another year at his home. Alas, he never succeeded in making a great composer of me, but I suspect that was not his aim. Instead, what I learned from him about music, about what it is for and what it is meant to do, is something that has enriched my life ever since.

I lost touch with Stephen in 1974, so he lives on in my mind as the energetic and youthful 50-year-old he was then. Many memories of him have been rekindled by reading this excellent book, and the truth is that he was an unforgettable man. The teaching rooms at the RCM were quite small, and he seemed to take up at least as much space as the piano. He had a loud voice, and as he got more and more passionate about his subject the voice become louder still. He was also extremely funny. In an interview in the book with Leonora Dawson-Bowling, his wife, harpsichordist Jane Clark, has this to say: ‘He had a huge sense of humour and, as all his friends said, he always laughed even more than the people he was telling the stories to.’ He would often repeat the punch line several times, even on those joyous occasions when the funny story was mine, and he seemed to laugh with his whole body, sometimes appearing to stop breathing. He cycled everywhere, including the five miles or so between his home in Barnes, Southwest London, and the RCM, cheerfully chaining his bike to whichever railings were near to hand. His comments and suggestions as he looked at my work were always of the most practical kind, and whilst there was not the slightest trace of a notion that I should compose music like his, the search for clarity and rhythmic drive typical of his own work were frequently at the basis of the observations he made. About the piano accompaniment of some songs I wrote he drew attention to ‘those hammy tenths in the left hand’; his point, and a crucial one, was that ‘I’m not convinced they’re really what you meant.’

To discuss music with Stephen Dodgson was to follow an incomparably rich trail of knowledge and ideas, though he never imposed his opinions on his students. One day I told him how much I enjoyed the music of Tchaikovsky. This was a rather unfashionable view at that time, but he was pleased, and told me that he thought the Violin Concerto was probably Tchaikovsky’s most beautiful work, even more beautiful than Brahms’s, he said, ‘which I also think is probably his most beautiful work.’ That comment widened my appreciation of both works and of both composers; I am unable to listen to this repertoire today without thinking of it. He encouraged me to get to know Shostakovich’s string quartets, which he considered to be more essential to an understanding of the composer than the symphonies. Small yet piercing comments about Debussy and Ravel have contributed enormously over the years to my own appreciation of those two masters. And I will always be in his debt for his role in my lifelong admiration for the music of Janáček. He once had a spare ticket for Jenůfa at Covent Garden and generously took me along. The effect the music had on him was almost physical. He then drove me home – I was also living in Barnes at the time – in what I seem to remember was a Renault 16 and a slightly unnerving journey. Five eminent contemporary musicians, quoted on the back cover of this book, describe Stephen Dodgson’s personality as ‘congenial’, ‘lively, intriguing and clearly lovable’ and ‘thoughtful, humorous and engaging’. I was just one of his many students, and I knew him for only a brief period, but these are good words to use, and many more along similar lines could easily be added.

–

This book, issued as a ‘Centenary Celebration’ of Stephen Dodgson (1924-2013), has been expertly edited and compiled by Oliver Chandler and Thomas Hyde. An introduction places Dodgson in the context of his contemporaries, reminding this reader of the multiplicity of composers, many of them neglected today, who were active in the second half of the twentieth century. A section entitled ‘The Composer’s Voice’ follows this, and these 30 or so pages are a particularly compelling part of the book. He was an eloquent man and a frequent broadcaster, and his written words are fascinating and full of insight into all aspects of music, and particularly his own. On the physical act of composing he is characteristically direct. Actually writing down all those notes, he says, is something that ‘… anyone can do with sufficient tenacity, some experience, and a reasonable training behind them.’ It’s rather like the work of an architect, he says: ‘Your musical score has a similar function to his plans and elevations. He has to be intelligible to the contractors. The eventual building will hopefully stand up, be practical, and the client may even perhaps like it.’ He is refreshingly dismissive of ‘inspiration’. ‘In so far as I’ve any confidence of experiencing even ten seconds of inspiration, I’m convinced that keeping steadily at work on one’s craft is the only hope that I may.’ He occasionally accepts to go into greater technical detail: ‘As a composer, I am in fact very particular about the spacing and colour of every sound. I never, in any medium, write music in a monochrome and score it afterwards.’ This does not mean that the instrumentation dictates the musical content. On the contrary, subtle variations in timbre between instruments ‘are only meaningful and appealing in relation to the stream of music … on which they are carried.’ In trying to define what he means by this ‘stream’, he writes this: ‘What I like to do is to discover myself through the medium and not impose myself on it.’ This, he says, is one aspect that explains why, not being a guitarist, he composed so much music for the instrument. This is not ‘because of what I said through it; but because I was prepared, eager, insistent that the message would look after itself if I only cared for the medium enough.’

This book, issued as a ‘Centenary Celebration’ of Stephen Dodgson (1924-2013), has been expertly edited and compiled by Oliver Chandler and Thomas Hyde. An introduction places Dodgson in the context of his contemporaries, reminding this reader of the multiplicity of composers, many of them neglected today, who were active in the second half of the twentieth century. A section entitled ‘The Composer’s Voice’ follows this, and these 30 or so pages are a particularly compelling part of the book. He was an eloquent man and a frequent broadcaster, and his written words are fascinating and full of insight into all aspects of music, and particularly his own. On the physical act of composing he is characteristically direct. Actually writing down all those notes, he says, is something that ‘… anyone can do with sufficient tenacity, some experience, and a reasonable training behind them.’ It’s rather like the work of an architect, he says: ‘Your musical score has a similar function to his plans and elevations. He has to be intelligible to the contractors. The eventual building will hopefully stand up, be practical, and the client may even perhaps like it.’ He is refreshingly dismissive of ‘inspiration’. ‘In so far as I’ve any confidence of experiencing even ten seconds of inspiration, I’m convinced that keeping steadily at work on one’s craft is the only hope that I may.’ He occasionally accepts to go into greater technical detail: ‘As a composer, I am in fact very particular about the spacing and colour of every sound. I never, in any medium, write music in a monochrome and score it afterwards.’ This does not mean that the instrumentation dictates the musical content. On the contrary, subtle variations in timbre between instruments ‘are only meaningful and appealing in relation to the stream of music … on which they are carried.’ In trying to define what he means by this ‘stream’, he writes this: ‘What I like to do is to discover myself through the medium and not impose myself on it.’ This, he says, is one aspect that explains why, not being a guitarist, he composed so much music for the instrument. This is not ‘because of what I said through it; but because I was prepared, eager, insistent that the message would look after itself if I only cared for the medium enough.’

The following ‘Memories and Tributes’ is a delightful collection of personal reminiscences. Pride of place, of course, goes to Jane Clark. From her we learn that he was an excellent cook, and that he was extremely proud of his vegetable patch, though he would only ever work there on a Sunday morning. On his working methods she tells us that ‘… he had amazing powers of concentration and he would always say, “You ought to be able to stop and answer the phone.” And he wouldn’t ever let us put the answer phone on … He could switch out and switch back in again.’ The writer and music critic, Paul Driver, who for a while rented the top floor of the Dodgsons’ home in Barnes, lets us into the conversations that arose spontaneously in the house: ‘His knowledge of music was a treasury to dip into … If he spoke, say, of EJ Moeran or Anthony Milner or Herbert Howells, it was with pointed anecdote that brought them into the room or hallway.’ Another aspect of Dodgson’s character is revealed by guitarist, Jonathan Leathwood. ‘In the course of making this album [Watersmeet, 2005] … we were privileged to have the composer listening to every take as it was made. And it is as a supremely attentive listener rather than as a director that his presence is felt everywhere. His prime concern was that we, the performers, could identify with the music at all times – as we shaped the music, it mattered even more to him that we were convinced by it than he was. He is generous with his own suggestions, sparing in his admonitions and happiest when the performers are excited by their own developing ideas.’

A little over half the book is taken up by the third section, ‘Perspectives on Stephen Dodgson’s Work’. A concise general introduction to the composer’s music by Robert Matthew-Walker is followed by a series of chapters in which experts explore the different genres in which Dodgson composed. The guitar music comes first, followed by the string quartets, the music for harpsichord, the operas, the songs, and Dodgson’s choral works. There then comes a fascinating chapter by Oliver Chandler on Dodgson’s musical language with particular reference to neo-classicism, and the section closes with a touching chapter recounting the composition and first performances of what was to be his final work, a short concerto composed and first performed by trumpeter Imogen Whitehead. These essays are written in an approachable style, though some technical knowledge will be of help in a few passages. In addition, because Dodgson was a prolific composer, the readers will frequently find discussions about music that is unfamiliar. One of the works I first got to know was the superb Duo Concertante for guitar and harpsichord. ‘When asked to write for harpsichord and guitar together, I simply couldn’t persuade myself that it could work. But Rafael Puyana and John Williams insisted that it did … The fascination is because they are similar yet different.’ Lance Bosman expresses some surprise that in this work the guitar is ‘forced into antagonism with the harpsichord’, something quite different from ‘the buoyancy and lyricism of the concertos’. Dodgson replies that he was indeed seeking ‘a relentless tension gradually broadening out at the end into a grand agreement.’ Anyone who has ever heard this terrific work will confirm the extent to which he achieved his aim. The recording of Duo Concertante by the magnificent players for whom it was written was deleted long ago and, as far as I know, has never appeared on CD. This is frustrating, but in recent years a large number of commercial recordings of Dodgson’s music has been issued, mostly on independent labels and many of them reviewed on this site.

This book is completed by a list of works, useful information about recordings and the book’s contributors, as well as a comprehensive index. The collection of photographs found in the middle of the book comes as a priceless bonus. The earliest ones are in black and white, and many of the later ones are very moving, one, in particular, with Imogen Whitehead in 2011 when dementia was no doubt beginning to take its toll. The book is beautifully produced and reasonably priced. It is a worthy celebration of its subject, a fine composer and erudite musician who was also a thoroughly nice man.

William Hedley

MusicWeb International