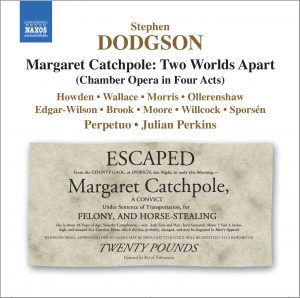

Stephen Dodgson’s reputation may lie primarily with his chamber and instrumental music but his diverse output included three chamber operas. The largest, Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart (1979), runs to almost three hours and four acts, with a large vocal cast of soloists, no chorus, and an accompanying instrumental ensemble of 11 players (wind quintet, string quartet, harp and double brass). The libretto, by Ronald Fletcher, is based on real events, recorded in the 19th-century novel The History of Margaret Catchpole by Richard Cobbold, the son of one of the main characters in the tale.

Stephen Dodgson’s reputation may lie primarily with his chamber and instrumental music but his diverse output included three chamber operas. The largest, Margaret Catchpole: Two Worlds Apart (1979), runs to almost three hours and four acts, with a large vocal cast of soloists, no chorus, and an accompanying instrumental ensemble of 11 players (wind quintet, string quartet, harp and double brass). The libretto, by Ronald Fletcher, is based on real events, recorded in the 19th-century novel The History of Margaret Catchpole by Richard Cobbold, the son of one of the main characters in the tale.

Dodgson’s vocal writing was much influenced by Britten – clearly audible in the treatment of East Anglian folk-like melodies in Act 1, for example – and the latter’s chamber operas (such as Albert Herring and The Turn of the Screw). There is a wonderful limpidity to Dodgson’s vocal lines, the words (usually set one note to a word, as annotator Richard Edgar-Wilson – who sings the role of Crusoe – observes) always clearly audible and never obscured by the accompanying ensemble. True, there is a lack of the type of theatrical grandeur one finds in Britten’s admittedly shorter operas. At times, Margaret Catchpole feels as much like a dramatic song-cycle or cantata as it does an opera.

The scenario is quite convoluted, involving smuggling, horse-theft, trials, death sentences and transportation to Australia, but centres ultimately on a love triangle focused on Margaret Catchpole, the teenage servant girl employed by the Cobbolds. Adored by the local miller’s son, John Barry, her affections lie rather with the smuggler, Will Laud. Their interactions drive the opera along, abetted by a vivid cast of supporting characters: the deeply unpleasant misogynist John Luff – Laud’s partner-in-crime – the mad retired sailor Crusoe, and the kindly Elizabeth Cobbold, Margaret’s employer and sometime protector, whose generosity is tested to its limits by Margaret’s infatuation with Laud, even after she steals a horse (end of Act 2) to gallop off to join him, for which she is sentenced to death twice in Act 3, having escaped from prison in between. By Act 4, Margaret has been transported to the penal colony in Australia, becoming an important chronicler of conditions there. The novel’s fanciful ending, contriving Margaret’s reunion and marriage to Barry, is wonderfully poetic in Dodgson’s sunlit setting, but there is no evidence that Margaret ever married or had children.

Kate Howden blends determination and misty-eyed vulnerability in a very rounded portrayal of Margaret. William Wallace and Nicholas Morris make a well-contrasted pair as the smugglers but it is Alistair Ollerenshaw who brings real nobility as John Barry. The Perpetuo ensemble play beautifully throughout, the whole directed impeccably by Julian Perkins. Naxos’s sound, recorded at the Snape Maltins, is first-rate.

Guy Rickards

Gramophone